HISTORY

The Pechanga Band of Indians has called the Temecula valley home for more than 10,000 years. Life on earth began in this valley at ‘Éxva Teméeku, the birthplace of the Káamalam (First Children). Teméeku was the place where the world as we know it came to be: events that took place here determined how some people became plants and animals, how people dealt with sickness and death, why some things could be eaten yet others could not, and all the other details of life in native California.

Pre-Contact (10,000+ Years Ago)

Groups of people now known as Indians have inhabited the Temecula Valley for thousands of years. We call ourselves Payómkawichum (the People of the West), and we are made up of seven bands: Pechanga, Pauma, Pala, Rincon, San Luis Rey, La Jolla, and Soboba. Evidence of our presence before the arrival of Europeans survives throughout the valley. Bedrock mortars, stone tools, pottery, and rock art are still found in Riverside and San Diego Counties. These artifacts prove that we have a long history and a rich culture that existed before the arrival of the Spanish Missionaries.

Through periods of plenty, scarcity and adversity, we have governed ourselves and cared for our lands. Over millennia, we came to understand the importance of natural cycles and learned how to manage our resources. We developed a variety of technologies, such as stone-tool manufacture, basket weaving, and pottery making, and our surplus goods were distributed along Southern California’s extensive trade routes.

Our society was organized to ensure that everyone had food and shelter, and everyone was raised to know what was expected of him or her. The stories of how the world was created have been passed down for generations, and these stories contain rules for proper behavior and the consequences of breaking those rules. Before the arrival of Europeans, the Payómkawichum understood their place in their world.

Post-Contact (1797)

The invasion of Spanish Missionaries – and each successive group of non-Natives – to the Temecula Valley had a devastating effect on the Payómkawichum, but we have survived every challenge. Generation after generation, we have grown and adapted to meet changing times and conditions. This land is witness to our story.

The Missionaries (1797-1834)

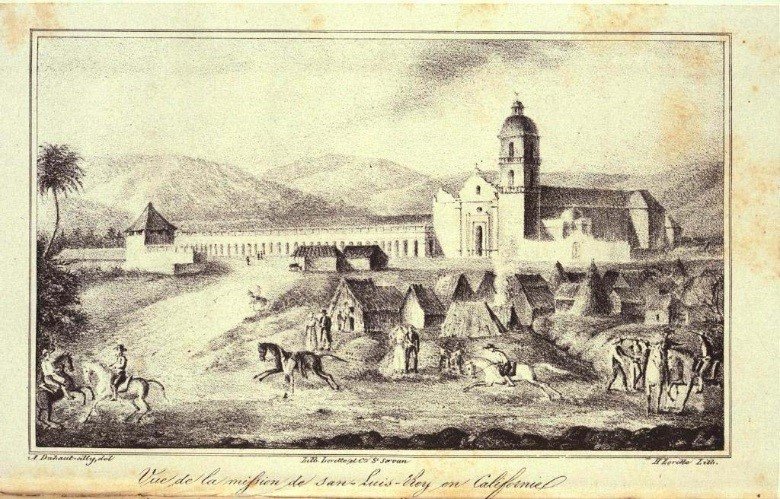

Europeans first arrived in the Temecula Valley in 1797. Father Juan Norberto de Santiago, a Franciscan priest, records passing through the Temecula Valley during an exploratory journey to identify possible sites for future missions. In 1798, the Spanish missionaries established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia within the borders of Luiseño Ancestral Territory. The Payómkawichum began to be called San Luiseños, and later, just Luiseños.

Europeans first arrived in the Temecula Valley in 1797. Father Juan Norberto de Santiago, a Franciscan priest, records passing through the Temecula Valley during an exploratory journey to identify possible sites for future missions. In 1798, the Spanish missionaries established Mission San Luis Rey de Francia within the borders of Luiseño Ancestral Territory. The Payómkawichum began to be called San Luiseños, and later, just Luiseños.

Life in the mission was hard for the Payómkawichum. Our ancestors were fed European foods that were not as nutritious as the fresh native foods they had eaten before. The poor diet, combined with new diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza, caused many Native people to get sick. Within a few decades of the founding of Mission San Luis Rey, several thousand Payómkawichum had died. Many of those who caught these diseases never lived at the mission, but they got sick from friends and relatives who had visited them.

The deaths of so many, combined with a strict social structure that separated people by age and gender, almost destroyed our culture. Stories and ceremonies were lost, and the language of the ‘atáaxum (Native people), was only used in secret. By the time the missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834, the population of the Payómkawichum has been decimated, and many ‘atáaxum were living in small isolated villages throughout the Temecula Valley. The Natives left behind when the Missions were abandoned returned to these small villages, or in some cases, started new villages of their own.

The deaths of so many, combined with a strict social structure that separated people by age and gender, almost destroyed our culture. Stories and ceremonies were lost, and the language of the ‘atáaxum (Native people), was only used in secret. By the time the missions were secularized by the Mexican government in 1834, the population of the Payómkawichum has been decimated, and many ‘atáaxum were living in small isolated villages throughout the Temecula Valley. The Natives left behind when the Missions were abandoned returned to these small villages, or in some cases, started new villages of their own.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and the Temecula Massacre (1847)

While most Payómkawichum did not participate in the Mexican-American war, many of them were directly affected by it. A series of events triggered by the Battle of San Pasqual (1846) led to the Temecula Massacre of 1847. Historical records suggest that the attack was a retaliation for the Pauma Massacre. During the Pauma Massacre, eleven Mexican soldiers who had participated in the Battle of San Pasqual were killed at Warner Hot Springs for stealing horses from the Pauma people.

While most Payómkawichum did not participate in the Mexican-American war, many of them were directly affected by it. A series of events triggered by the Battle of San Pasqual (1846) led to the Temecula Massacre of 1847. Historical records suggest that the attack was a retaliation for the Pauma Massacre. During the Pauma Massacre, eleven Mexican soldiers who had participated in the Battle of San Pasqual were killed at Warner Hot Springs for stealing horses from the Pauma people.

One day in early January, a troop of Mexican soldiers and their Native accomplices trapped a group of Temecula people in a local canyon and killed many of them. More than one hundred Temecula Indians were killed in the Massacre, but we will never know the exact number. When the Mormon Battalion reached Temecula around January 25, 1847, many of the dead were still unburied, and a massive rainstorm the day before had washed some of the bodies away. The men in the Battalion helped our ancestors bury the remaining dead before continuing their journey to San Diego. Victims of the Temecula Massacre now rest at the Old Temecula Village Cemetery.

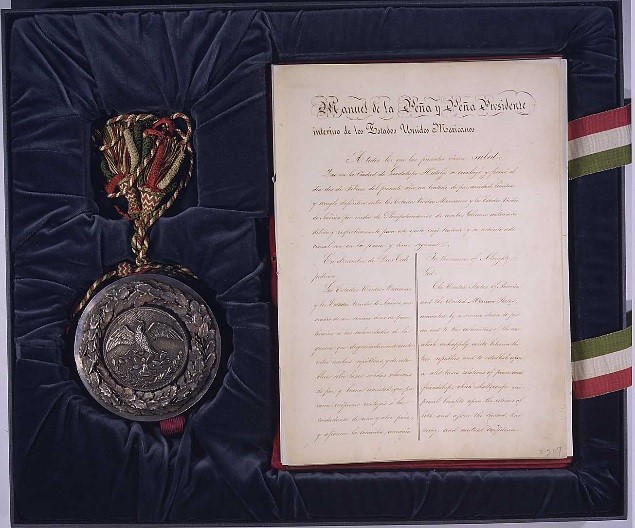

The Mexican-American war ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California was part of the huge territory that Mexico ceded to the U.S. under the terms of the Treaty. The Treaty specified that Native people in the new U.S. territory were to have the same legal rights they had enjoyed as Mexican citizens; instead, the U.S. government chose to withhold citizenship from Native Californians, and as a result, most of them lost their right to own property, too.

The Mexican-American war ended in February 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. California was part of the huge territory that Mexico ceded to the U.S. under the terms of the Treaty. The Treaty specified that Native people in the new U.S. territory were to have the same legal rights they had enjoyed as Mexican citizens; instead, the U.S. government chose to withhold citizenship from Native Californians, and as a result, most of them lost their right to own property, too.

California Statehood (1850) and the Treaty of Temecula (1852)

One of the unfortunate effects of statehood on California’s Native people was the passing of An Act for the Governance and Protection of Indians on April 22, 1850. This Act and its 1860 Amendments permitted American citizens “to have the care, custody, control and earnings of such [Indian] minor until he or she obtain the age of majority." The later amendments allowed adult Indians to be “indentured” (enslaved) in the same way. Though the Act of 1850 was intended to keep homeless Indians off the streets, unscrupulous people used it as an excuse to kidnap ‘atáaxum and sell them to unaware or uncaring masters.

One of the unfortunate effects of statehood on California’s Native people was the passing of An Act for the Governance and Protection of Indians on April 22, 1850. This Act and its 1860 Amendments permitted American citizens “to have the care, custody, control and earnings of such [Indian] minor until he or she obtain the age of majority." The later amendments allowed adult Indians to be “indentured” (enslaved) in the same way. Though the Act of 1850 was intended to keep homeless Indians off the streets, unscrupulous people used it as an excuse to kidnap ‘atáaxum and sell them to unaware or uncaring masters.

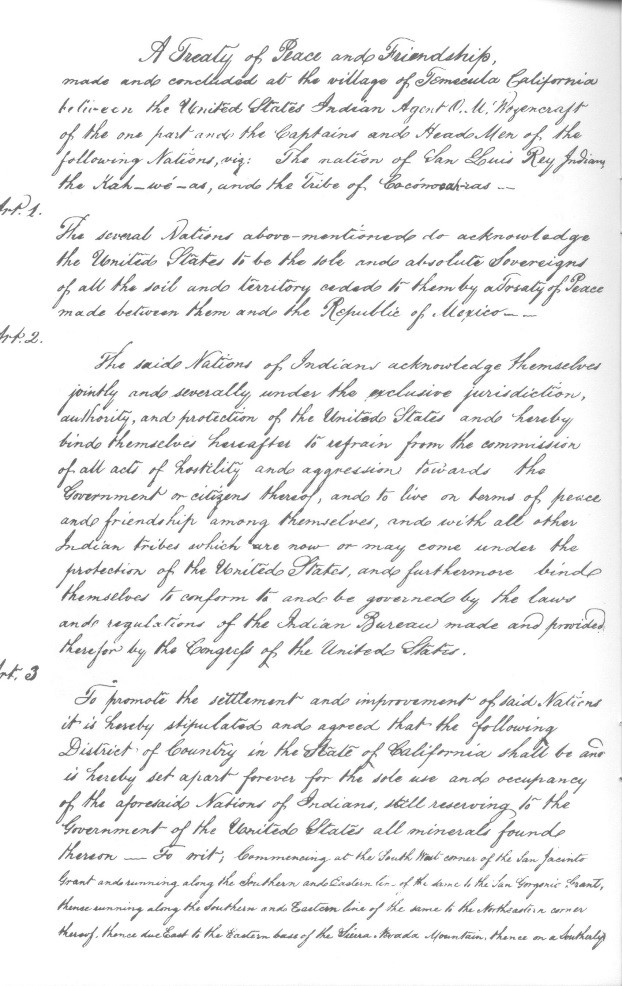

Shortly after California became a state, U.S. Indian agents came to the Temecula Valley to “make peace” with the ‘atáaxum here. The Treaty of Temecula was one of 18 unratified treaties signed by representatives of nearly 200 California tribes throughout the state. Ysidro Toshovwul and Lauriano Cahparahpish are Pechanga ancestors who signed the Treaty in 1852.

The treaties ensured that large tracts of land around the state would be reserved for the sole use of the Native groups to whom they belonged (with the exception of mineral rights and public roads). In return, the government promised to provide a specific amount of livestock and goods. However, the U.S. Senate refused to ratify any of the treaties and the original documents were considered “lost” until 1905. By the time the unratified treaties were rediscovered, most of the reservations in and near Temecula had already been established and inhabited for decades, and the original agreements were no longer valid.

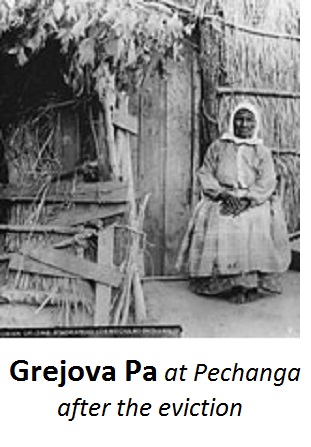

The Temecula Eviction (1875)

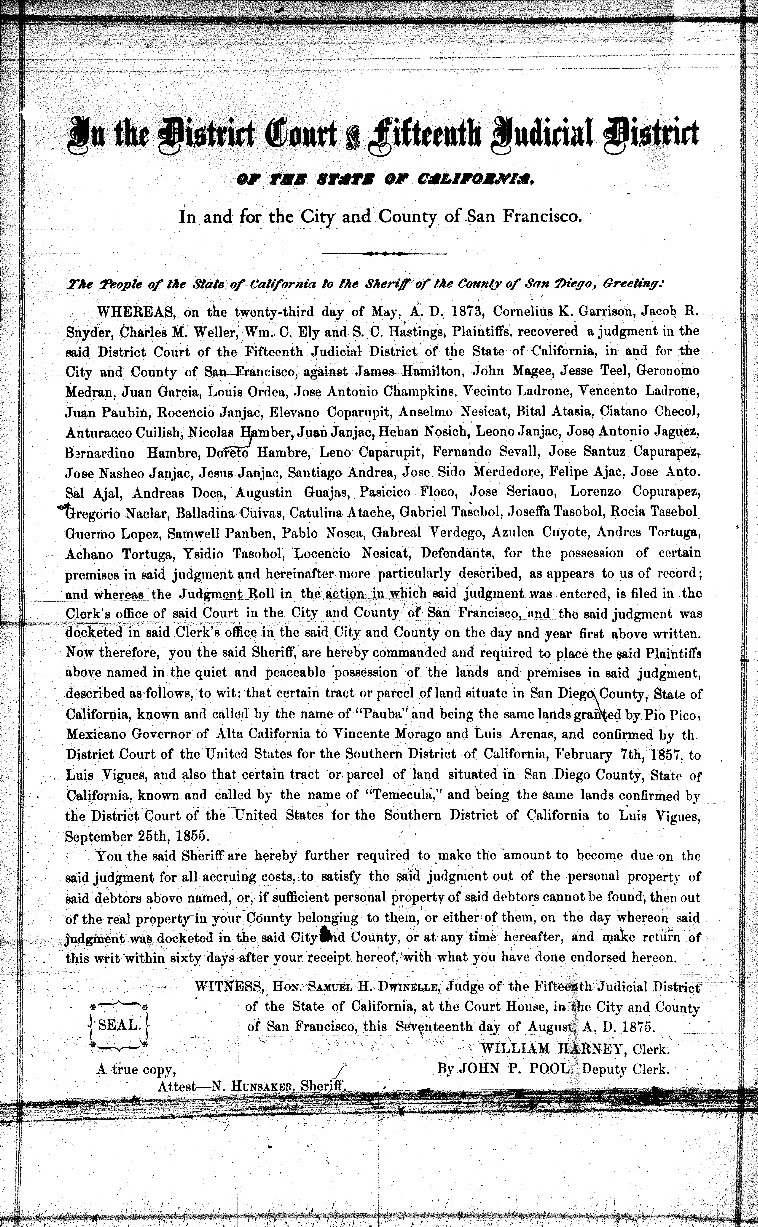

A group of Temecula Valley ranchers petitioned the San Francisco District Court for permission to evict the Payómkawichum who lived in the village on the Little Temecula Rancho. The judge agreed to the eviction, ignoring the fact that our ancestors had lived there for generations under the terms of a Mexican land grant. The eviction took place between September 20 and 23, 1875. José Gonzales, Juan Murrieta, Louis Wolf, and several other local landowners formed an armed posse, assisted by Sherriff Hunsaker of San Diego. The posse members loaded the contents of each home into wagons and dumped everything about three miles to the south, forcing the Indians to follow the wagons on foot.

A group of Temecula Valley ranchers petitioned the San Francisco District Court for permission to evict the Payómkawichum who lived in the village on the Little Temecula Rancho. The judge agreed to the eviction, ignoring the fact that our ancestors had lived there for generations under the terms of a Mexican land grant. The eviction took place between September 20 and 23, 1875. José Gonzales, Juan Murrieta, Louis Wolf, and several other local landowners formed an armed posse, assisted by Sherriff Hunsaker of San Diego. The posse members loaded the contents of each home into wagons and dumped everything about three miles to the south, forcing the Indians to follow the wagons on foot.

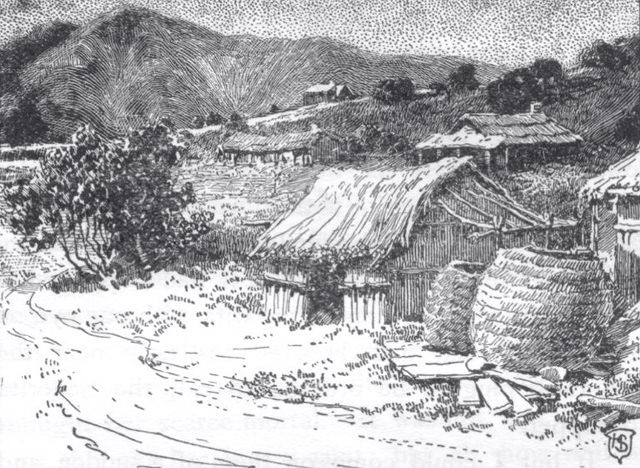

Despite losing nearly everything they owned, the Temecula people found ways to survive. At first, the evictees stayed on John Magee’s land, close to the place where the posse had driven them. Magee was married to a Temecula Indian woman named Custoria Nesecat, and he was sympathetic to the ‘atáaxum. Later, most of our ancestors moved upstream to a small, secluded valley near a spring called Pecháa'a (from pechaq = to drip). This spring is where the Pechanga band gets its name: Pecháa’anga means "at Pechaa'a; at the place where water drips." (Click here for more information about the Temecula Eviction.)

Creation of the Reservation (1882)

On June 27, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Executive Order that established the Pechanga Indian Reservation. The reservation’s name comes from the place where the Temecula Indians settled after they were evicted from the village at Little Temecula.

On June 27, 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed the Executive Order that established the Pechanga Indian Reservation. The reservation’s name comes from the place where the Temecula Indians settled after they were evicted from the village at Little Temecula.

Author Helen Hunt Jackson was instrumental in securing reservation land for the Pechanga people. She visited Temecula shortly after the Eviction. At that time, Jackson was a U.S. government agent investigating the living conditions of Southern California Indians. She included several first-hand accounts of the Eviction in her report, which helped sway government opinion in favor of our people.

The Kelsey Tract (1907)

Though life on Pechanga Reservation seemed to start well for the Pechanga people, a series of droughts and setbacks left them on the brink of starvation in the early 1900s. Most of our ancestors had to find work off the reservation to survive. Many of them found work on local ranches and farms as cowboys, field hands, and servants. Vail Ranch, in particular, hired a significant number of ‘atáaxum from the Pechanga, Pala, Rincon, Soboba, and Cahuilla reservations.

Though life on Pechanga Reservation seemed to start well for the Pechanga people, a series of droughts and setbacks left them on the brink of starvation in the early 1900s. Most of our ancestors had to find work off the reservation to survive. Many of them found work on local ranches and farms as cowboys, field hands, and servants. Vail Ranch, in particular, hired a significant number of ‘atáaxum from the Pechanga, Pala, Rincon, Soboba, and Cahuilla reservations.

In 1906, U.S. Indian Commissioner C.E. Kelsey suggested that the reservation needed additional farmland if our ancestors were going to survive. In 1907, the U.S. government purchased 235 acres of land next to Pechanga Reservation that came to be known as the Kelsey Tract. Despite the nearby spring (called Túuchaana), there wasn’t enough water to irrigate the entire property reliably. To make improve the water supply, the Pechanga people dug a well and installed a windmill-powered pump. The land was put into trust for Pechanga under the U.S. Interior Department's Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

The Mission Indian Federation (1919) and U.S. Indian Termination Policies (1953 – 1964)

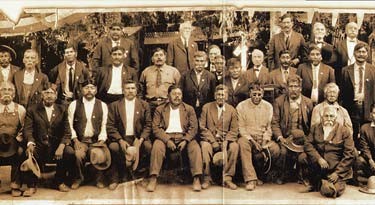

The Mission Indian Federation (MIF) was the first Native American Civil Rights group founded and operated by Southern California Indians. Membership was open to everyone, though only Native people could vote on resolutions. The MIF’s primary goals were freedom from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and full citizenship rights for all Native Americans. Many Pechaángayam were active members of the organization, and some held leadership positions in the organization, including Eduardo Garcia, Antonio Ashman, and Dan Pico.

The Mission Indian Federation (MIF) was the first Native American Civil Rights group founded and operated by Southern California Indians. Membership was open to everyone, though only Native people could vote on resolutions. The MIF’s primary goals were freedom from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and full citizenship rights for all Native Americans. Many Pechaángayam were active members of the organization, and some held leadership positions in the organization, including Eduardo Garcia, Antonio Ashman, and Dan Pico.

The MIF fought for Indian Civil Rights for over fifty years. The organization was at its height when the Indian Citizenship Act was passed on June 2, 1924. However, this Act did not affect all ‘atáaxum equally, so the MIF was still active in Southern California through the 1950s and 1960s, particularly during the U.S. Government’s Indian Termination Policy period. The Mission Indian Federation finally dissolved in the early 1970s. (Click here for more information about the Mission Indian Federation.)

The MIF fought for Indian Civil Rights for over fifty years. The organization was at its height when the Indian Citizenship Act was passed on June 2, 1924. However, this Act did not affect all ‘atáaxum equally, so the MIF was still active in Southern California through the 1950s and 1960s, particularly during the U.S. Government’s Indian Termination Policy period. The Mission Indian Federation finally dissolved in the early 1970s. (Click here for more information about the Mission Indian Federation.)

During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States created several laws that have come to be known as the Indian Termination Policies. These laws effectively forced the assimilation of over 100 formerly recognized Native American tribes by closing their reservations and cutting them off from the services they had received through the federal government. The government believed the closures were justified because a 1943 Senate report stated that living conditions on many reservations were so poor that forcing Indians to become part of mainstream America could only be an improvement. The Indian Termination Era officially ended with the passage of the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 and the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, but many California Natives are still effected by the laws made during Termination.

The Pechanga tribe was never slated for Termination, but they were affected by Public Law (PL) 280, which was passed in 1953 during the Termination era. Promoted as a way to reduce BIA presence on Indian reservations, PL 280 placed reservation Indians under state jurisdiction for most criminal and some civil offenses while reducing their access to federal services. Though PL 280 has been amended many times, it still affects people living on California reservations today.

Pechanga Today (1988 – present)

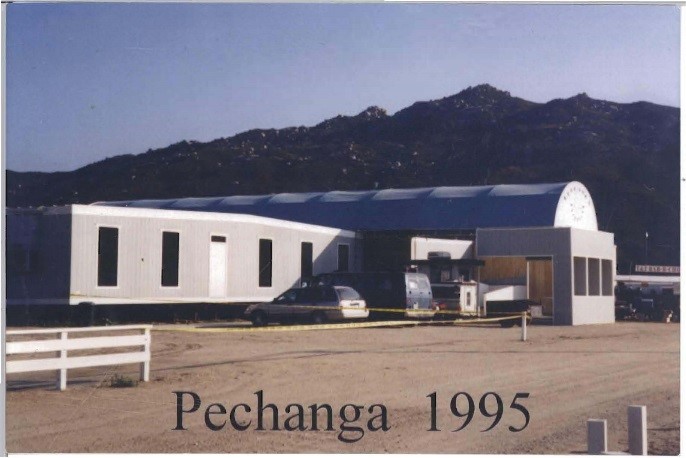

The last thirty years have brought many changes to the lives of the Pechaángayam. The Indian Gaming Acts of 1988, 1998, and 2000 gave tribes in California the right to open gaming facilities on their lands. In 1995, Pechanga opened its first gaming facility, which has expanded over the last twenty years to include a hotel, spa, and golf course. Pechanga’s gaming operations and related investments have allowed us to provide our people with more opportunities than they have had in the past, including better healthcare and access to higher education.

The last thirty years have brought many changes to the lives of the Pechaángayam. The Indian Gaming Acts of 1988, 1998, and 2000 gave tribes in California the right to open gaming facilities on their lands. In 1995, Pechanga opened its first gaming facility, which has expanded over the last twenty years to include a hotel, spa, and golf course. Pechanga’s gaming operations and related investments have allowed us to provide our people with more opportunities than they have had in the past, including better healthcare and access to higher education.

In 1988, the passage of the Southern California Indian Land Transfer (Public Law 100-581) Act added 303 acres along Pechanga's northern boundary. The addition of the Great Oak Ranch property in 2003 and the purchase of Pu’éska Mountain in 2012 expanded the reservation further. Today, the gross total land area of Pechanga Reservation stands at 7,080 acres. Our ancestral territory extends across the borders of Riverside and San Diego counties, and we have a responsibility to preserve and protect this land . Today, Tribal Government operations such as Pechanga's monitor programs and cultural resource management exist to fully honor and protect the land and our cultural sites.

Indian Gaming in the Temecula Valley has not only helped to improve the lives of Pechanga people, but also our local community. The casino at Pechanga employs thousands of local people and generates millions of dollars in tax revenue every year. The tribe actively donates money to local charities and public works projects. Most recently, we collaborated with the people of the Temecula Valley to fight the Liberty Quarry development. The project would have destroyed Wexéwxi Pu’éska (Pu’éska Mountain), a very sacred place in the Luiseño religion, and it would have created a lot of air pollution in the valley. After a five-year battle, we purchased the mountain, so both it and the people of the valley are safe from the damage the proposed quarry would have caused. ( Click here for more information about Pu’éska Mountain.)

We, the Pechaángayam, are optimistic about the future. We will continue to help our people and the communities of the Temecula Valley remain self-sufficient and forward thinking for many years to come.